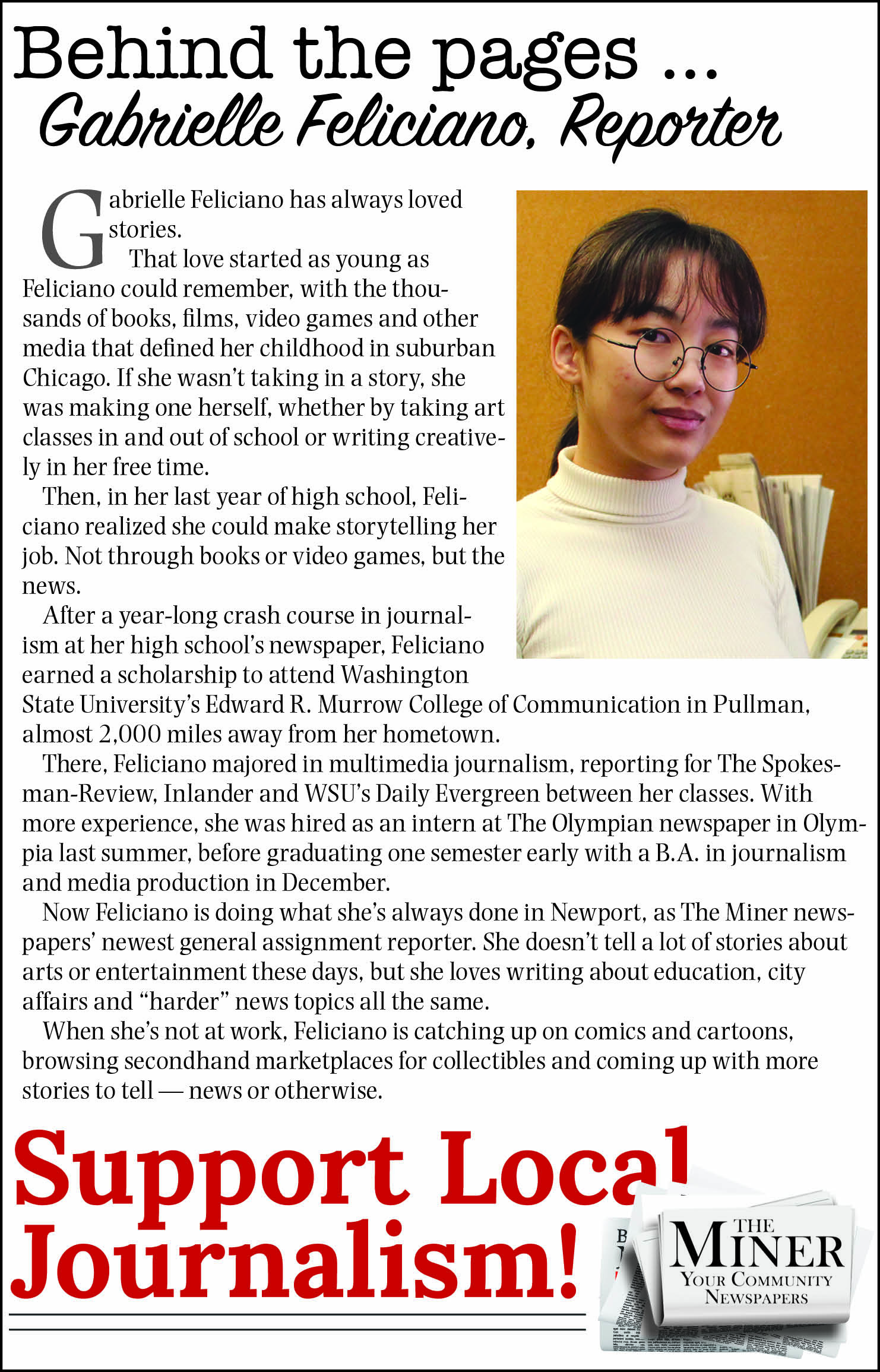

Alan Myers always knew he wanted to get back to eastern Washington.

For one thing, the longtime Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife police officer grew up in Idaho, back when Eagle was more farm town than suburb, and he still has family all over the Gem State.

For another, this is where the 52-year-old cut his teeth as a game warden, patrolling the woods from postings in Newport and later Clarkston.

When the top WDFW Police job in the eastern region opened up, he saw a chance to return.

In July, Myers took over as WDFW’s police captain for the 10-county eastern region, overseeing a team of 17 officers who patrol the vast territory.

During a meet-and-greet with reporters last week, he said people generally do not understand much about game wardens and what they do, and he wants to help change that.

“We go under the radar,” Myers said. “My job will be to help improve that visibility for Fish and Wildlife officers.”

There are 166 officers working across the state and their jobs are not limited to chasing poachers and checking fishing licenses, though that is a not insignificant part of the job.

Alongside Washington State Patrol, WDFW Police is one of two state-level police agencies, and the ones most likely to be found patrolling alone in remote places.

They are sometimes the first to respond to a wildfire and they are often involved in search-and-rescue efforts. They have drones that help track down lost hikers and a swiftwater rescue team. They investigate wolf attacks on cattle and deal with bears and cougars that show up in the wrong places.

Myers has been with WDFW for 25 years. He became a game warden after a stint in the Navy and studying sociology and biology at the University of Washington. He worked in Snohomish County briefly, then Newport and then Clarkston, where he stayed for seven years.

A job in WDFW’s headquarters office in Olympia took him back to the west side, where he trained officers on Tasers and defensive tactics. After that, he became police captain in the North Puget Sound Region, where he stayed for six years. The last five years, he worked on special projects in the Olympia office.

His return to eastern Washington puts him in the center of a number of thorny issues, the most promi- nent being the state’s dealings with wolves. When he left Clarkston in 2011, there were just a few known wolves in the state, and the southeastern corner was thought to be empty of them.

At the end of 2024, WDFW’s biologists counted at least 230 wolves, and there are packs spread throughout the state’s eastern third, including multiple packs in the southeastern corner.

Dealing with wolves forces wildlife managers to walk a fine line between protecting the species and easing the burden on cattle producers, Myers said. His focus will be on making sure investigations into wolf attacks on livestock are the best they can be.

“It’s not just very comprehensive and thorough,” he said, “but it’s also very quick and timely.”

Staffing is another challenge Myers sees for WDFW Police. He said the agency had been working to beef up its enforcement ranks for years until the Legislature put a freeze on hiring new officers last spring as part of a raft of budget cuts for WDFW and other state agencies.

In eastern Washington, that has left Ferry County without a full-time game warden. Myers said officers in Stevens County try to cover Ferry County, but that is too big an area to patrol part-time.

“That’s a long way to travel to cover and a lot of territory that desperately needs a Fish and Wildlife officer presence,” Myers said.

He also thinks the agency could benefit from shoring up its enforcement presence on the Snake River in southeast Washington, where wardens deal with issues related to Endangered Species Act-protected salmon.

He said the agency hopes to work with the Legislature during the next session to get the OK to hire more officers.

More officers is not solely about having a larger force to catch wrongdoers, at least in Myers’ eyes. He said WDFW Police officers exist to help the public enjoy the vast variety available in the state — a variety he enjoys, too, as a warmwater angler, novice archery hunter and passionate bird hunter.

“You can go within just a few hours from hunting pheasants to being on the other side of the mountains throwing out a crab pot,” Myers said. “There’s nowhere else in the world that’s like this.”

.png)