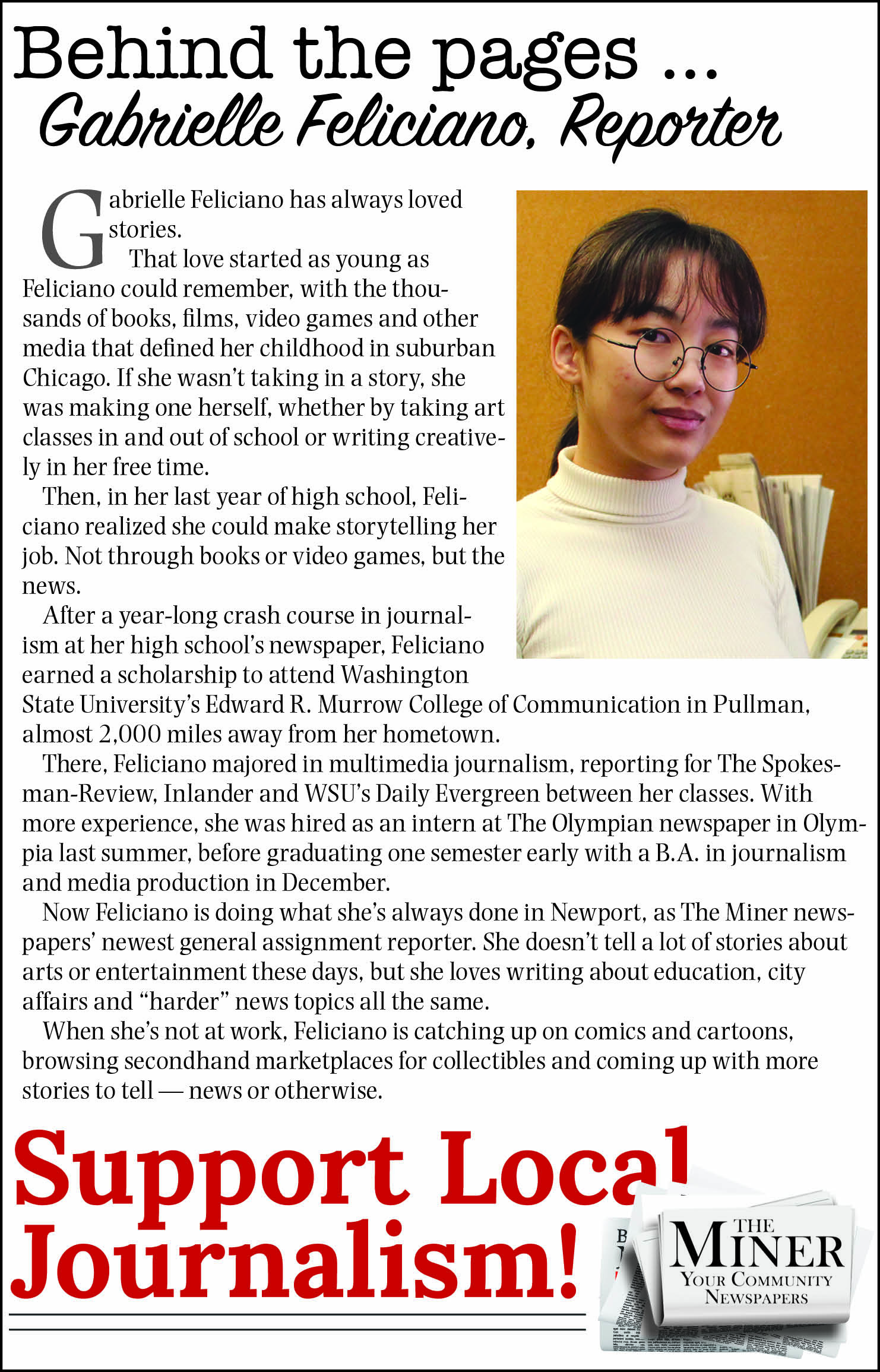

Cusick veteran overcomes brain injury to earn PhD

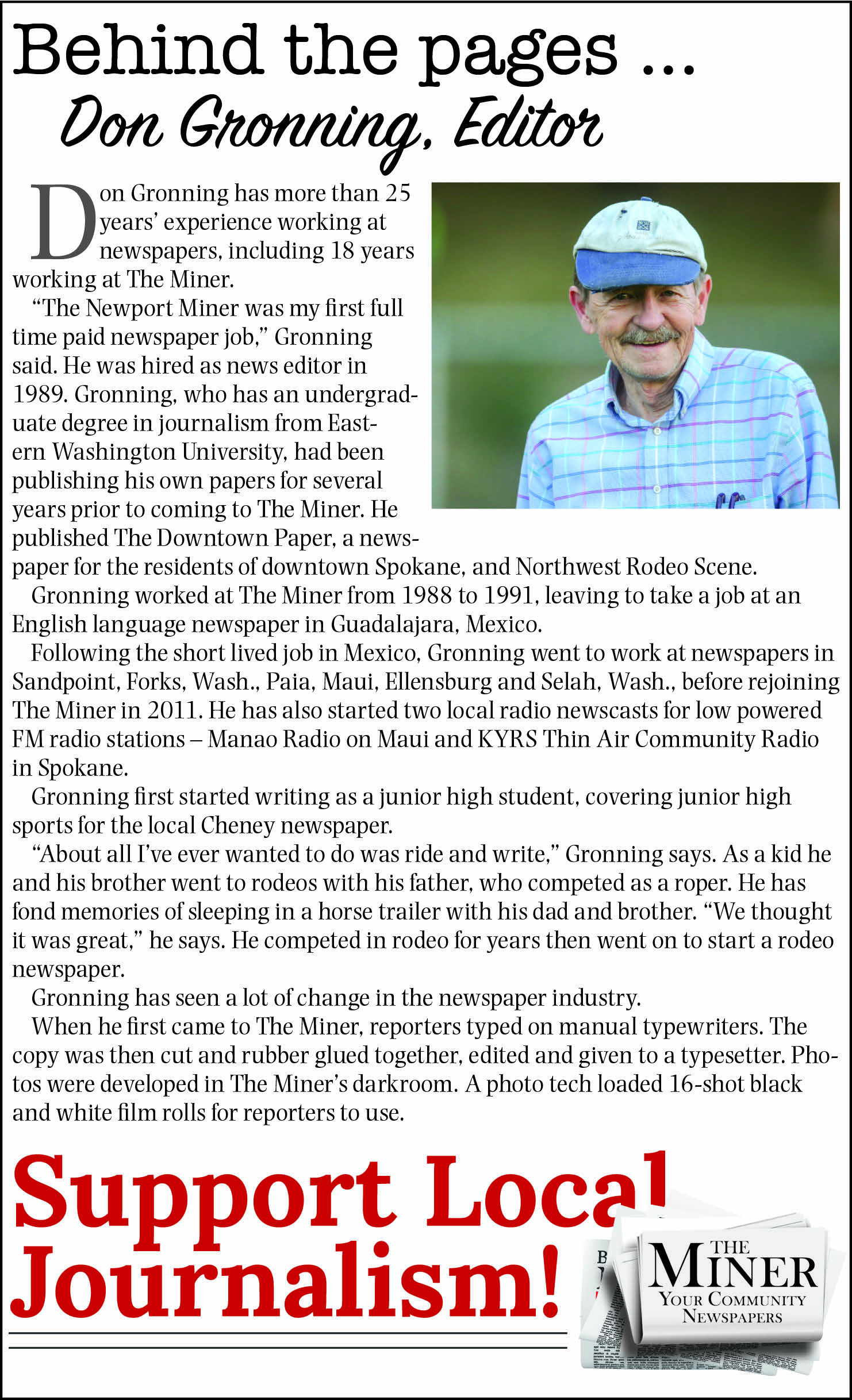

CUSICK — Ben Richards is eating a steak tortilla at a restaurant in Newport, the 2000 West Point ring on his right hand as prominent as a Super Bowl ring. His service dog, Bronco, is quietly curled under the table.

Between bites, he’s talking about the process he went through to receive a doctorate degree from Kansas State University after completing a dissertation on Economic Warfare in World War II.

Richards, 49, is medically retired from the U.S. Army. He experienced traumatic brain injury after two concussions received in bombings three weeks apart, one from a suicide bomber driving a car and the second from an improvised explosive device. Bunco, his service dog, senses when something is wrong with Richards’ body and alerts him, giving him time to prepare.

For Richards, getting a doctorate degree, not an easy task under any circumstance, was not a small accomplishment.

At the time he was injured in 2007, he was a Captain, commanding Bronco Troop, First Squadron, 14th Cavalry Regiment in Iraq, according to a 2007 New York Times story about Richards’ initiative to partner with local Sunni Muslim militias to defeat the local branch of Al Qaeda.

The outlook for someone with Richards’ condition wasn’t encouraging. It took some time for the Army to recognize the extent of Richards’ injury. He was initially diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, which he had, but the brain injury wasn’t diagnosed as being as serious as it was.

He had been accepted to a teach at West Point prior to the explosions.

“They accepted me, then I was injured afterwards,” he says. “I really only taught for a few months, then it was clear I wasn’t really going to be able to do anything meaningful for the Army, so they medically retired me.” He left the Army as a Major in 2012.

He endured the effects of the concussion — an inability to sleep, constant headaches and pain. The outlook wasn’t good.

“The understanding of brain injuries and science at the time was that not only would I not get better or improve, but that I would just get worse over time,” he says. The goal in life then was to manage that decline. “The new normal is kinda the code phrase that they like to use for that, kind of manage that in a way basically that you don’t kill yourself too fast.”

Richards wasn’t just struggling with just the brain injury and its symptoms. Everything changed for him and his family. He and his wife, Farrah, have four children.

“Most individuals in my situation ended up being divorced,” he says. “I was really fortunate that my wife was a glutton for punishment and decided to stick around.”

Things started to turn around after he was admitted to the National Intrepid Center of Excellence, a traumatic brain injury center in Bethesda, Maryland in 2011.

“I was able to get some kind of novel experimental care,” he says, hyperbaric oxygen treatment therapy. After trying virtually all the other therapies available, it was the HBOT that made the difference. HBOT involved breathing 100% oxygen at an increased atmospheric pressure for an hour in a special chamber.

“Pre-treatment and post-treatment brain scans showed HBOT caused a 20% increase in brain function and neuro-psych testing conducted at Walter Reed in 2011 and 2015 verified that I experienced meaningful gains in IQ in the areas where I had the most degradation due to the TBI,” Richards says. He and his family moved to Cusick in 2018.

He had roughly a 45-point increase in IQ five years after injury, something that was thought to be nearly impossible at the time. With the improved brain function, he wanted to challenge himself.

“The decision for me to get a doctorate was really more about a vision quest,” he says. “To try to redefine my life and who I was after having lost a lot of my identity.”

So he plunged himself into the work, which was more challenging for him than it would have been before he got hurt.

“A three-year process for a dissertation is kind of the normal,” Richards says. “Mine probably took double that.”

Getting a doctorate degree is demanding, says Dave Smith, Newport School District Superintendent. He received a doctorate in education from Washington State University in 2011.

“I worked on mine for about four straight years,” he says, while holding down a job. It was challenging.

“It’s every single weekend, every night, just reading and reading,” Smith says. The classes and the dissertation are arduous, especially the dissertation. “It takes a lot of writing.”

Smith published a 114-page manuscript on Leadership in Rural School Districts.

Richards also engaged in lots of research and reading for his doctorate. His major field was American history and he had three minor fields.

“For each of the fields you’ll have to read somewhere in the realm of 30 to 50 books, in addition to the coursework, to become proficient in what historians have written in each of those fields,” he says. That culminates in a full week of examinations — a week of three- or four-hour examinations in which a written work is required.

After all that, the dissertation is written. In history, the requirement is to create an original work of history or some aspect of history that no other historian has written about. For that Richards reviewed thousands of original documents.

Richards originally was going to write about America’s economic warfare on Japan during all of World War II. In during the research, he found he couldn’t address the topic in just one book-length manuscript. So he focused on Economic Warfare during World War II. He gave his first public presentation on the work last week.

Richards is continuing his vision quest, even though he now has the PhD.

He will be presenting at the Historical Analysis Annual Conference in late October in Washington, D.C., a conference hosted by the Dupuy Institute, a think tank founded by a famous military historian Colonel Trevor Dupuy. He will also be lecturing on World War II industrial mobilization and economic warfare at George Mason University in Virginia in January.

He is giving presentations on the dissertation and analyzing his experiences as a Troop Commander directing one of the most decisive battles of Operations Iraqi Freedom that resulted in the defeat of the terrorist group al Qaeda in Iraq.

Richards is not completely healed. “I still have significant and challenging health challenges resulted from my wounds in Iraq,” he says. But he regained enough quality of life and function to earn a PhD and contribute to the community through service as a youth minister and Boy Scout leader for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints and Protect Pend Oreille, among other groups.

“And most importantly to have meaningful and positive relationships with my incredible wife, who had to go through a lot, and four children,” he says. It’s fair to say he’s come a long way.

.png)